Why Developers Should Understand Business Models

How engineering decisions shape margins, pricing and churn and why developers must understand business models.

Introduction: The Myth of the “Purely Technical” Developer

For years, organisations have operated under a quiet but persistent assumption: developers build, business teams sell, finance measures, and leadership decides. The lines are clean. The responsibilities are separate. The incentives are different.

But modern technology companies — and increasingly, non-technology companies that rely on software — do not function in neat silos. Software is not a supporting tool anymore. It is the product, the distribution channel, the customer experience, and often the revenue engine itself.

When software becomes the business, developers are no longer just writing code. They are shaping margins, influencing pricing power, affecting customer retention, and determining long-term viability.

Yet many engineers are never taught how business models work.

This is not a criticism of developers. It is a systemic blind spot. Computer science programmes teach algorithms, distributed systems and optimisation — but rarely contribution margins, churn rates or cost of goods sold. Inside companies, developers are given backlogs, not balance sheets.

The result? Technically elegant systems that quietly erode profitability. Architectures that constrain pricing flexibility. Features that increase complexity and drive customer churn.

Understanding business models is not about turning developers into accountants. It is about equipping them to make better technical decisions — decisions that strengthen the economic foundations of the products they build.

In this article, we will explore three central arguments:

- Engineering decisions directly affect margins.

- Architecture choices shape and limit pricing strategy.

- Technical complexity significantly influences churn.

Developers who understand these forces become exponentially more valuable — not just to their teams, but to the entire organisation.

Engineering Decisions Affect Margins

Margins are often discussed in finance meetings, but they are built — or destroyed — in engineering meetings. At its simplest, margin is revenue minus cost. In software businesses, revenue is driven by pricing and customer volume. Costs are driven by infrastructure, support, maintenance, development time and operational overhead. Every engineering decision influences one or more of these cost drivers.

When engineers choose a particular database structure, cloud provider, or third-party service, they are shaping the cost base of the product. A system that requires heavy compute power, excessive storage, or constant scaling under load increases operational expenditure with every new customer. Conversely, efficient architecture, thoughtful caching strategies and optimised queries reduce the cost per user, improving gross margin as the company grows.

Even decisions that seem minor at development stage can have compounding financial consequences. For example, shipping features without clear boundaries or documentation often increases support tickets. Each ticket requires human time. As the user base expands, support teams must grow. What began as a small technical shortcut becomes a recurring operational expense.

Maintenance is another silent margin driver. Complex, fragile systems demand constant attention. Engineers spend time fixing regressions instead of building value-generating features. That lost velocity is not abstract; it translates into delayed releases, missed opportunities and increased payroll costs relative to output.

Developers may not sit in financial review meetings, but their daily choices determine whether the company operates efficiently or struggles under rising costs. High-margin software businesses are rarely accidental. They are the result of disciplined engineering decisions that consider performance, scalability and long-term sustainability.

Ultimately, margin is not only a financial metric. It is a reflection of technical design quality.

Infrastructure Choices and Cost of Goods Sold

In SaaS businesses, infrastructure is effectively part of the cost of goods sold. Cloud hosting, database queries, storage, third-party APIs — these costs scale with usage.

Consider two teams building the same product:

- Team A builds for efficiency, optimises queries, designs caching layers, and reduces unnecessary compute usage.

- Team B prioritises speed of delivery, accepts redundant processing, and layers tools without evaluating cost implications.

If both teams sell at £30 per month, but Team A costs £5 per user to operate while Team B costs £15, the difference in gross margin is transformative.

High-margin businesses reinvest in growth. Low-margin businesses cut corners or collapse under scaling costs.

Developers who understand margin ask different questions:

- What does this architectural decision cost per user?

- Will this feature increase infrastructure spend disproportionately?

- Are we building for long-term operational efficiency?

These are not finance questions. They are engineering questions with financial consequences.

Maintenance Burden as a Hidden Cost

Technical debt is often discussed as a productivity issue. But it is also a margin issue. Every workaround, rushed feature and piece of duplicated logic is not just a compromise in elegance — it is a future financial liability.

When teams move quickly without structural discipline, they create systems that are harder to understand, extend and stabilise. Over time, this translates directly into more developer hours spent fixing rather than building. Engineers who could be working on revenue-generating improvements instead find themselves tracing legacy bugs, untangling dependencies or rewriting brittle components. That lost time carries a real cost in salaries, opportunity and slowed innovation.

Slower release cycles are another hidden consequence. As complexity grows, testing becomes harder, deployments riskier and regressions more frequent. Each release requires more coordination and caution. The organisation becomes hesitant. What once took days begins to take weeks. In competitive markets, that delay can mean missed customer needs and lost market share.

Increased risk of outages compounds the problem. Fragile systems fail more often, and failures erode trust. Downtime not only disrupts users but can trigger refunds, service credits and reputational damage. Each incident adds operational cost while reducing perceived value.

When a company must maintain a large engineering team simply to keep an unstable system running, margins shrink. Payroll expands without proportional revenue growth. In contrast, well-designed systems enable leaner teams to deliver more value with greater confidence and speed.

Code quality, therefore, is not just craftsmanship or pride in clean architecture. It is margin protection. It preserves engineering velocity, reduces operational risk and ensures that future effort compounds rather than drains resources. Over time, disciplined engineering is not just good practice — it is financially strategic.

Feature Decisions and Support Costs

Features that seem minor at the development stage can create disproportionate support burdens.

Imagine introducing deep customisation options without guardrails. Customers configure complex workflows, misconfigure settings, and require constant support assistance.

Support headcount grows. Response times slow. Satisfaction drops.

A technically flexible system may appear powerful, but if it increases support overhead, it compresses margins.

Developers who understand business models consider:

- How will this feature affect support load?

- Does this increase operational complexity?

- Can we design this in a way that reduces confusion?

Simplicity is often more profitable than flexibility.

Architecture Impacts Pricing Strategy

Pricing is rarely viewed as an engineering concern. But architecture either enables or restricts pricing flexibility.

How a system is built determines how it can be packaged, tiered and monetised.

Monolith vs Modular Systems

A tightly coupled monolithic system may be efficient to start with, but it can limit pricing experimentation.

If features cannot be easily isolated, metered or disabled, it becomes difficult to offer:

- Tiered pricing plans.

- Usage-based pricing.

- Add-on modules.

- Enterprise upgrades.

A modular architecture, by contrast, allows features to be packaged differently. It enables differentiated value propositions across customer segments.

For example:

- Basic users access core functionality.

- Professional users unlock automation features.

- Enterprise clients gain advanced integrations.

Without architectural separation, this flexibility becomes technically painful or impossible.

Pricing strategy lives downstream of architecture.

Usage-Based Pricing and Metering

Modern SaaS businesses increasingly adopt usage-based or hybrid pricing models. Charging per API call, per transaction, per gigabyte processed or per active user aligns revenue more closely with the value delivered. However, this model depends entirely on accurate tracking and metering. Without reliable usage data, pricing becomes guesswork — and guesswork erodes trust, revenue accuracy and customer confidence.

If usage measurement is not designed into the architecture from the beginning, retrofitting it later can be extremely complex. Systems that were never built to log granular activity may lack clear boundaries between features, users or actions. Attempting to layer billing logic onto such systems often results in brittle workarounds, inconsistent reporting and disputes over invoices. What should be a strategic pricing shift becomes a costly technical overhaul.

Developers who understand pricing implications think differently during system design. They build with observability in mind. They ensure that usage events are structured, traceable and attributable to specific customers or accounts. They separate concerns so that billing logic can evolve independently of core functionality. They anticipate that pricing models may change as the business grows.

Accurate tracking also allows companies to understand cost drivers. When engineers can see which actions consume the most compute or storage, they can optimise accordingly. Pricing becomes not just a revenue mechanism but a feedback loop between product, engineering and finance.

Pricing agility becomes a competitive advantage. Companies that can experiment with tiers, bundles or usage thresholds respond faster to market demands. Architecture determines whether that agility exists — or whether the business is locked into a rigid model defined by early technical shortcuts.

Scalability and Enterprise Sales

Enterprise clients expect reliability, scalability and security.

If the architecture cannot support:

- High concurrency,

- Data isolation,

- Compliance requirements,

then enterprise pricing becomes inaccessible.

A technically constrained product cannot command premium pricing.

On the other hand, systems designed for robustness and scalability can justify higher price points.

Architecture does not just determine how a product runs — it determines what it can be worth.

Technical Complexity Influences Churn

Churn is often treated as a marketing or customer success issue. But a significant portion of churn originates in technical complexity.

Customers rarely cancel because of one bug. They cancel because using the product feels difficult, unpredictable or frustrating.

Engineering design choices directly shape user experience.

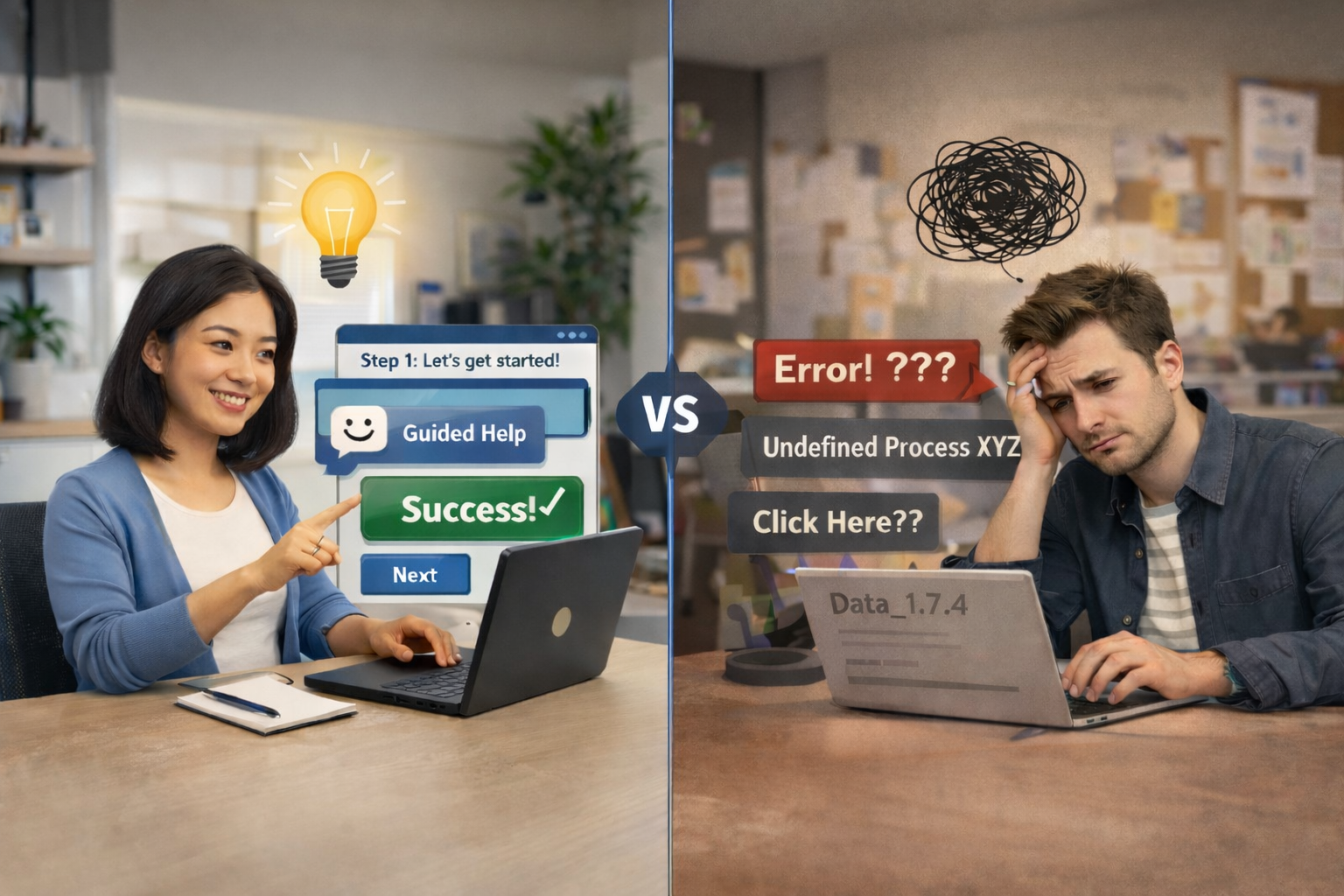

Cognitive Load and Onboarding

Complex workflows increase cognitive load. Users must learn too much before achieving value.

If onboarding requires lengthy tutorials, support tickets or hand-holding, adoption suffers.

Developers influence:

- How intuitive interfaces are.

- Whether workflows are streamlined.

- Whether error messages are helpful.

Products that teach users naturally reduce churn. Products that overwhelm users increase it.

Technical complexity becomes customer friction.

Performance and Reliability

Slow load times, intermittent failures and inconsistent behaviour erode trust.

Trust is central to retention.

Engineers may view minor latency issues as acceptable trade-offs. Customers may interpret them as unreliability.

When technical systems are unstable, churn rises — even if the core value proposition is strong.

Reliability is not just a technical metric. It is a retention lever.

Integration Fragility

Many SaaS products depend on integrations with third-party tools. If those integrations are fragile or difficult to configure, customers become frustrated.

Every broken integration increases perceived risk.

If technical architecture makes integrations brittle, churn increases.

Conversely, robust APIs and thoughtful error handling build confidence and reduce churn.

Developers shape that experience at the foundation level.

The Strategic Advantage of Business-Aware Developers

When developers understand business models, their thinking shifts.

They begin to ask:

- How does this feature contribute to revenue?

- Does this increase cost per user?

- Will this improve retention?

- Does this unlock a new pricing tier?

They move from task execution to strategic contribution.

Better Prioritisation

Not all features are equal.

Business-aware developers understand that:

- Features increasing retention may be more valuable than flashy new additions.

- Improvements that reduce infrastructure costs may be strategically critical.

- Reducing support burden may create margin expansion.

This perspective improves roadmap discussions.

Stronger Cross-Functional Collaboration

When engineers speak the language of margins and churn, collaboration improves.

Finance teams appreciate cost awareness.

Product teams benefit from pricing-informed architecture.

Leadership trusts engineers who understand commercial realities.

Communication becomes clearer because incentives align.

Long-Term Product Thinking

Short-term technical shortcuts may accelerate delivery but damage long-term economics.

Developers who understand business models weigh trade-offs differently.

They recognise that:

- A slightly slower launch may result in significantly better margins.

- Simplifying a feature may reduce churn.

- Investing in scalable architecture may unlock enterprise revenue.

They optimise for sustainability, not just speed.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

The technology landscape has changed. For years, abundant venture funding allowed companies to prioritise growth above all else. Speed was rewarded. Market share mattered more than margins. Inefficiencies could be absorbed under the promise of future scale.

That environment no longer dominates. Venture funding is tighter. Investors are asking harder questions about profitability, unit economics and long-term sustainability. At the same time, customers have more alternatives than ever before. Competitors can emerge quickly, and switching costs are often low. Loyalty is earned continuously, not assumed.

In this environment, economic discipline is no longer optional — it is foundational.

Products must operate efficiently, ensuring that each additional customer contributes positively to the bottom line rather than increasing operational strain. They must scale sustainably, without infrastructure costs spiralling faster than revenue. They must retain customers consistently, because acquiring new users is far more expensive than keeping existing ones. And they must adapt pricing dynamically, responding to changing market expectations and usage patterns without undergoing technical overhauls.

Developers are central to all four of these requirements. Efficiency is rooted in architecture. Scalability depends on system design. Retention is shaped by reliability, performance and usability. Pricing flexibility is determined by how well the system supports metering and modularity.

The era of growth-at-any-cost masked inefficiencies because capital covered the gaps. Today, those inefficiencies are exposed. Fragile systems, bloated infrastructure costs and rigid architectures quickly become liabilities rather than temporary inconveniences.

Engineering decisions are financial decisions. Each design choice either strengthens the company’s economic resilience or weakens it. In a more disciplined market, developers are not just builders of software — they are guardians of sustainability.

Reframing the Role of Developers

This is not about burdening engineers with financial spreadsheets or expecting them to become part-time accountants. It is about expanding awareness. When developers understand how the business operates economically, their technical decisions become sharper, more intentional and more aligned with long-term success.

Developers should understand gross margin and how it is calculated — not in abstract theory, but in relation to their own product. They should know the company’s pricing structure: what customers pay for, how value is packaged, and where revenue actually comes from. They should be aware of churn rates, because retention reflects whether the product is truly delivering sustained value. And they should understand the cost drivers of their infrastructure — what increases hosting bills, what scales efficiently, and what silently inflates operational spend.

With that context, technical trade-offs gain clarity. Decisions about performance optimisation, feature scope, refactoring or architectural investment are no longer purely technical debates. They are strategic choices with measurable impact.

When engineers understand the economic engine behind the product, they design systems that support it rather than strain it. They think beyond functionality towards sustainability. In doing so, they become builders of value — not just builders of software.

Conclusion: Code Is a Commercial Act

Every line of code has economic consequences.

Some lines increase operational efficiency.

Some enable premium pricing.

Some reduce churn.

Others quietly inflate costs and complexity.

Developers who understand business models see beyond implementation. They see impact.

They recognise that architecture shapes revenue potential. That technical complexity shapes customer retention. That engineering discipline protects margins.

The most successful technology companies are not those with the most features. They are those with the most economically aligned systems.

Developers sit at the centre of that alignment.

Understanding business models is not optional strategic polish. It is a core professional advantage.

In modern product organisations, technical excellence without business awareness is incomplete.

The future belongs to engineers who understand not just how systems work — but how businesses work.